Robert Schultz is an American composer, arranger, and editor. He is also co-founder of Schultz Music Publications and creator of the Robert Schultz Piano Library. This library includes more than 500 publications of classical works, popular arrangements, and Schultz’s original compositions in editions for pianists at every level. In addition to piano work, Schultz has also produced original orchestral works, choral and vocal works, chamber music and works for solo instruments.

I spoke to Robert about his background and experience in engraving music notation.

When did you first become interested in notation music?

I guess it goes back to when I was a composition student at West Virginia University studying with Thomas Canning in the 1970s. Everything was done by hand in pencil or pen and you naturally began to look for ways to write more efficiently and accurately so that what you had written could be easily read by those attempting to learn and perform the music.

Copy machines in those days were scarce and not very good so even creating multiple copies of music was a challenge. The music school had a device, I believe it was called a Bruning machine, that would burn copies onto special, oversized paper, so we could use that for orchestra scores, but the originals had to be created with pen on transparent paper. It was a grueling process and I’m really glad we don’t have to do that anymore.

When did you first become serious about engraving standards?

Again, while a student at WVU, studying both piano and composition. Acquiring scores meant buying real editions that would become lasting library editions, and I found the look and quality of those scores to be fascinating. Things like the Schnabel Beethoven volumes published by Belwin Mills, the Durand editions of Debussy’s piano music, and others, were very beautiful and inspiring and this became a goal—to be a published composer and see my music in similar editions.

At that time there was no possibility of having such an edition of one’s music without a publisher, so that became the goal. I carried that care and concern with me when I became senior keyboard editor for Columbia Pictures Publications and pushed for the highest engraving standards possible.

What notation textbooks were influential for you?

There were no notation textbooks that I referred to as a student, only scores. Everything you needed to know existed in published scores so the library was the primary reference for anything you needed to know beyond what you had on hand. I still tell students that most of their questions about how and where to place things in their scores can be answered by checking a quality music edition.

There was one book that we kept in the office at Columbia Pictures Publications and did refer to—The Art of Music Engraving & Processing by Ted Ross.

Can you talk a little about your role at Columbia Pictures Publications?

After moving to Miami in 1978 I became a staff arranger at Columbia Pictures Publications, a position I held for one year and was then promoted to senior keyboard editor and also became their featured keyboard writer. The company’s primary activity was in the area of popular music, creating sheet music editions of current pop hits, movie music, TV music, etc.

I wrote a tremendous number of piano arrangements during the next 10 years, more than 2,500 piano solos and duets at all levels of difficulty from beginner to advanced/professional. I directed a staff of in-house arrangers and several freelance arrangers who would transcribe single songs and albums for the piano/vocal releases, the primary sheet music edition.

When the company acquired the rights to a new hit song or movie theme, I and others on the staff would immediately begin work on the arrangements that the music dealers and buyers expected to be released, and these would be completed, engraved and printed in a matter of a few days. Single sheet music editions would later be combined and released in collections.

For me, this was the beginning of the Robert Schultz Piano Library which evolved to include not only popular music but jazz arrangements, classical editions, Christmas music and my original piano works. I held this position until 1990 when I left the office to work from my home studio and focus entirely on writing and continuing to create new editions as the company’s featured piano writer. By this time, having acquired Belwin Mills, the company name had changed to CPP/Belwin. In the 90s the company was acquired by Warner Bros. and 10 years after that Alfred became the owner.

What process was involved in engraving music at Columbia?

The primary in-house engraving system was unique and a little bizarre. It involved placing white plastic noteheads with stems on a black felt board. The board resembled the kind that used to be used in hotel lobbies to display messages, letters inserted in horizontal slots. Our engraving boards had white staff lines running across with slots in between where you would insert the tabs on the back of the plastic notes. The engravers would place the white plastic noteheads and accidentals on the staves and when all was in place the board would be carried to a room where it was photographed. That process yielded a white page with black staff lines and notes. But it was far from finished.

From there the photograph page went to the “finisher” who would use a Rapidograph pen to draw ties, slurs, crescendo/decrescendo wedges, and anything that could not be done in step 1. Dynamic marks, accents, staccato dots and similar marks were added from rub-off sheets. Terms and phrases were typed onto gum stock, cut out with an Exacto knife and pasted onto the page. Then it would have to be proofread and any corrections generally involved using whiteout and ink.

It was difficult and the result was never elegant unless you slaved over it, but we did get music out to the public surprisingly quickly. We also used outside engravers for some projects, including one in Korea that made gorgeous engravings entirely by hand, but it would take months to get those back. Another South Florida engraver used an IBM music typewriter, a system that had its own quirks and problems.

What was your first introduction to Finale?

When Columbia Pictures Publications acquired Belwin Mills, they acquired a computerized engraving system as part of the deal. It was rudimentary but a great step up from the photographic system they had been using. It still required some hand finishing but the result was excellent. It must have been sometime in the late 1980s that they started using Finale as well.

They must have started with the earliest Finale releases and I began to see the results when I proofread my arrangements and transcriptions. As I recall, in those early days there was quite a learning curve for the engravers as they started to work with Finale so I and the other writers continued to submit pencil manuscripts to be engraved. I marked corrections on the proofs and learned what things were easy for the engraver using Finale to fix and what things were tougher.

Even in those early days, the look of the final product was excellent and I was so pleased that I could ask for things to be corrected such as beam slants and the amount of space between staves and systems, or even changing the layout when a system was too tight or too open. That was an amazing step in the right direction.

When did it become part of your ordinary workday? Was the transition contentious or otherwise difficult?

My personal work with Finale began in 2002 when I bought a Mac G5 and the 2002 version of Finale. I immersed myself in the tutorials and in less than a week had input a set of original works from manuscript that I had planned to use as a test project. And I never looked back. From that time on everything I wrote was set in Finale, although I still make initial rough drafts with pencil and manuscript paper, then use the speedy entry tool to input the notes in Finale.

Can you share a favorite Finale tip?

My first tip would be to encourage a new user to do the tutorials and read the instructional material before getting started. A lot of people tend to skip the software manuals these days and I feel that is not the way to start out with Finale. I met a music teacher once who complained that Finale couldn’t create odd rhythmic groupings other than a triplet!

Of course, my advice was to read the manual, and that there really wasn’t anything Finale couldn’t do, which I believe. I’m a big fan of metatools and am glad that I learned early on how much time it can save to create keyboard shortcuts for the elements I use regularly, particularly for inserting expressions.

I’ve always been picky about beam slants so I run the Patterson Beams plugin with my preferences before finalizing a score, and love to watch how that works. I also get a lot of use of the note mover tool to create cross-staff beams in piano scores. It takes a few steps but is well worth it.

What do you like (or dislike) about Finale?

Having come from a background where everything was done by hand, being able to extract parts from a score is nothing short of a miracle. If you’ve never copied parts from a big orchestra score that you just finished writing you may not be able to fully appreciate this, but it’s a big deal.

Even things like inserting a measure after you’ve worked in an area of a score, or experimenting with a different key signature just to see if it might read better, are amazing tools and advances compared to the way things used to be done. These things save so much time and I’ve been able to write a lot more music because of them.

What is your workflow today, from inception to the printed page?

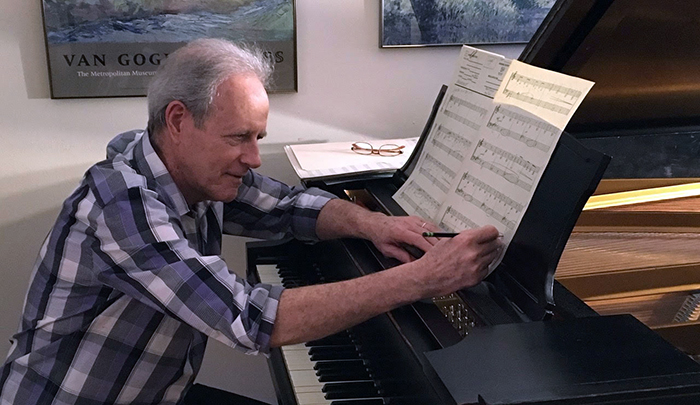

For me, everything begins by working at the piano. I have a superb 1912 Steinway A that I have owned since I was in college and much of my work has initially emerged from that instrument’s sound. I have always made sketches and drafts at the piano then transferred the writing to a finished score.

My Finale scores are the final product for everything that is published in Schultz Music Publications—piano editions, chamber music, choral and orchestral works. My wife, Tina Faigen is an expert concert pianist with an innate sense about piano editing, so she sees everything before it is released. A second set of eyes is always helpful and I know that if I’ve missed something she will spot it.

When I’m doing projects for other publishers such as FJH, Alfred, Online Sheet Music, I send them the finished Finale files and they paste them into their own templates. I still have to proofread to make sure everything comes through intact, but except for some tweaking there are rarely any issues. I do work with the publisher’s editor who handles and coordinates the project with the in-house engravers and art department.

What current projects are you working on?

I just began work on a commission for a trio for piano, clarinet and cello. This is my second work for this ensemble, Zaffiro Trio out of the University of Pittsburgh, and I’m glad to be contributing in an area where there is not a wealth of repertoire. There are a few other new works that are in their final stages but have not yet been released: Eight Songs for Soprano and Piano on poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay, a commission for a soprano here in Pittsburgh; Solitaire for Piano, a one-movement piece for the right hand alone, written for a friend in Detroit who has M.S. and has lost the use of her left arm.

I just sent Finale files to FJH for a Christmas edition in a new piano series they asked me to create. I also budget time when I can to go back into my early catalog and engrave in Finale those works that still exist only in manuscript. So trying to schedule and balance the time for composing, publisher projects and maintaining the website for Schultz Music Publications keeps me busy and inspired.

Special thanks to Robert for taking the time to share his experiences with us all.